In August 1821, a letter arrived in Calcutta from across the seas. Written by a Muslim woman named Pearbux, it contained a desperate plea: “This is the worst place that ever could be expected. I am traited no better than a slave.”

Pearbux was an ayah—an Indian nursemaid—working for a merchant family in early colonial Sydney. Her letter, sent to her former employer George Chisholm, would become one of the most compelling voices we have from these marginalised women who traversed the British Empire as domestic servants.

Today, Professor Victoria Haskins of the University of Newcastle is piecing together the hidden history of these travelling ayahs and their Chinese counterparts, amahs, who worked in colonial Australia. Her Australian Research Council-funded project, led with Claire Lowrie and Swapna Banerjee, is revealing a crucial chapter in Australia’s settler colonial past that has remained obscured for two centuries.

“These women have been hidden in our history, and finding them is a slow process of winnowing records that often fail to register the presence of women or servants at all, let alone their names and their lived experiences,” Haskins explained in her recent Allan Martin Lecture at the Australian National University.

A Personal Journey Into the Archive

Haskins’s interest began with a family legend about her great-grandmother’s grandmother, Maggie Goldie, who was supposedly sent from India to Scotland as a child accompanied only by her beloved ayah. What seemed like a fantastical tale became the spark for a major research project when Haskins realised there was indeed a whole history of Indian nursemaids travelling the empire with British families.

The word “ayah,” of Portuguese origin, came to refer to the indispensable women who served British families in India. They were often the only female servants in households where men traditionally dominated domestic service—their employment emerging in direct response to European women’s demands for female staff.

While the United Kingdom acknowledges these workers with a blue heritage plaque in London, their presence in Australia has been virtually unknown. Yet the evidence is there for those who look carefully enough.

Following the Maritime Routes

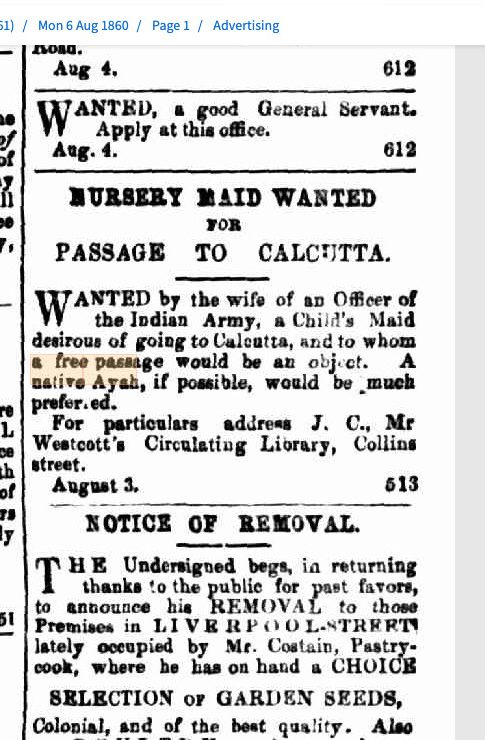

Ayahs came to Australia in various ways, particularly during the early colonial period when significant maritime trade connected India and the Australian colonies. Some travelled with families relocating from India. Others were professional seafaring childcarers who advertised their services in colonial newspapers, making multiple journeys over many years.

Haskins discovered their traces in unexpected places. While reading historian Alan Martin’s biography of Henry Parkes, she noticed something he hadn’t emphasised: alongside 24 Eurasian men who migrated from Madras in 1854 were several women—three wives, a young single mother, and a 15-year-old girl, all listed as servants or ladies’ maids.

The research demanded painstaking work. “I’ve had to go back and re-read previous histories and pull out the same sources that have been looked at before to shake out these precious stories,” Haskins notes.

Voices of Resistance

What emerges from these archival fragments are stories of remarkable agency and resistance. In 1819, three years before Pearbux wrote her letter, another group of Indian domestic workers took action against the same employer family—the Brownes of Sydney.

Thomassee (or Tamasee), who described herself as a “lady’s dresser,” along with two teenage girls named Faktim and Pari, had travelled from Calcutta with their mistress Sophia Browne in 1818. According to their testimony, all had been with the family since infancy. Yet they complained vehemently of Sophia’s physical and verbal abuse.

The women prepared a written petition to Governor Macquarie, asking him to “dissolve the bond of slavery” and allow them to return to their native country. Their petition, combined with complaints from male servants, persuaded Macquarie to summons the Brownes to court. The workers won their case and returned to India.

Pearbux, employed by the same family, likely stayed behind to care for Anne, the Brownes’ eldest daughter, who had suddenly married a ship’s captain. When Anne died nine months later—her newborn surviving only through a wet nurse—Pearbux found herself trapped. The family refused to release her or pay her passage home.

That’s when she wrote to Chisholm, who forwarded her letter to the new Governor, Thomas Brisbane. The intervention worked. In February 1822, Pearbux was discharged and provided passage back to Calcutta.

The Challenge of Reconstruction

Working with such fragmentary evidence presents profound methodological challenges. Haskins argues that historians must employ imagination—not as fantasy, but as method—to connect the dots between verified facts.

“When we work with lives like those of Pearbux, we’re faced with gaps so wide that the archive seems to fall silent altogether,” she explains. Following historian Saidiya Hartman’s approach, Haskins believes the task goes beyond simply retrieving hidden voices: “We’re called to enlarge our imagination, to contemplate what might have happened, what could have happened, what probably did happen.”

This imaginative work becomes a vehicle for empathy—one of history’s most powerful gifts. “Imagination and empathy are two of the things most precious to the human condition, and two of the things that the world needs more of right now,” Haskins emphasises.

Why These Stories Matter

In Australia, where Indian people now make up the second-largest migrant population after the English, this long historical presence remains largely unknown. Post-Federation, even as the infamous dictation test sought to exclude non-white migrants, ayahs continued entering the country in the company of their employers, becoming subjects for media fascination and strict government surveillance.

These stories matter not only as recovery projects but as challenges to how we understand Australian history itself. They reveal the essential care labour that sustained colonial households, the global circuits of empire that connected distant places, and the ways marginalised women navigated and resisted oppressive systems.

“As history, these stories matter in their own right. These women deserve to be heard,” Haskins concludes. “But my purpose goes beyond recuperation. I want us to reflect about what happens when we go back and revisit histories we think are familiar and settled.”

Sometimes, the most important stories are built upon the smallest traces—a letter sent across the seas, a name in a shipping record, a petition to a colonial governor. In reconstructing these fragments, we don’t just recover the past. We reclaim our capacity for empathy and imagination in the present.