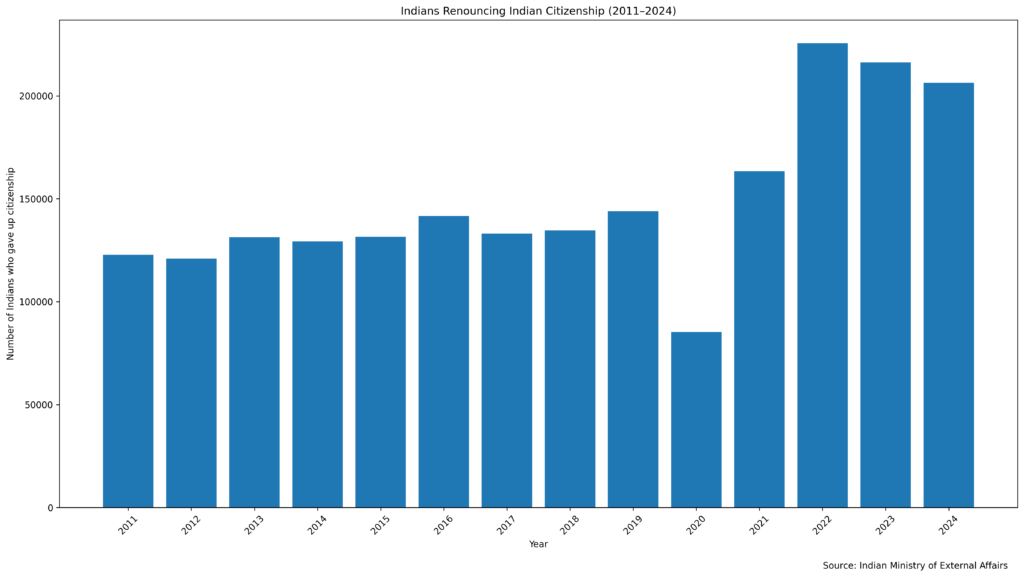

More than 2.06 million Indians have renounced their citizenship over the past 14 years, with the pace accelerating sharply since the Covid-19 pandemic, according to official figures tabled in India’s Parliament.

Data released by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) shows that 206,378 Indians gave up their citizenship in 2024, following 216,219 in 2023 and a peak of 225,620 in 2022. Annual renunciations have remained above 200,000 for three consecutive years, marking a clear break from the long-standing pre-pandemic trend.

Between 2011 and 2019, the number of Indians renouncing citizenship was relatively stable, fluctuating between 120,000 and 145,000 a year. That pattern was disrupted in 2020, when global travel restrictions and consular shutdowns during the pandemic caused the figure to fall to 85,256, the lowest level in a decade. Once borders reopened, deferred applications were processed in large volumes, driving a sharp rise from 2021 onwards.

In total, almost one million Indians have surrendered their citizenship in the past five years alone, accounting for close to half of all renunciations recorded since 2011, according to the MEA’s written response to a question in the Rajya Sabha.

Australia among key destinations

While the Indian government does not publish country-by-country data in its parliamentary replies, the MEA has confirmed that Indians have taken up citizenship in at least 135 countries worldwide, with major destinations including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia.

For Australia, the trend intersects with broader migration patterns. Indians are now Australia’s second-largest migrant community and among the fastest-growing sources of skilled migrants and international students, particularly in health, information technology, engineering and higher education.

‘Personal reasons’, but structural drivers persist

Responding to questions in Parliament, Minister of State for External Affairs Kirti Vardhan Singh said the reasons for renouncing Indian citizenship were “personal and known only to the individuals concerned”, adding that the government viewed the global Indian diaspora as an asset in a knowledge-based economy.

However, reporting by India Today and The Times of India points to a combination of structural and lifestyle factors driving the surge. These include stronger employment protections, higher wages, cleaner environments, more reliable infrastructure, and clearer pathways to permanent residency and citizenship in destination countries .

A key legal factor is that India does not permit dual citizenship. Under Section 9 of the Citizenship Act, 1955, Indians who voluntarily acquire another nationality automatically lose their Indian citizenship. While Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) status allows long-term residence and visa-free travel, it does not confer political rights such as voting or holding public office, leaving many long-term migrants with little practical choice but to formally renounce their Indian passport.

Skilled and affluent migrants dominate the flow

Although the MEA does not maintain occupation or income data on those renouncing citizenship, international research suggests the outflow is disproportionately skilled and affluent.

According to the United Nations, India has remained the world’s largest source country of international migrants, with an overseas population of around 17.5 million as of 2019. In the United States, 81 per cent of Indian-born adults hold at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with around 36 per cent of the US-born population, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

Economist and former prime ministerial adviser Sanjaya Baru has described the trend as a “secession of the successful”, citing Morgan Stanley data indicating that around 23,000 Indian millionaires left the country between 2014 and 2023.

Policy implications and political debate

Despite India remaining the world’s largest recipient of remittances—with the World Bank estimating inflows of about US$125 billion in 2023—the sustained rise in citizenship renunciation has become a growing political issue.

Opposition figures have questioned whether the trend reflects deeper concerns about urban liveability, education, healthcare, environmental quality and long-term economic security, particularly for younger professionals and families. Analysts cited in recent media reports note that the persistence of post-pandemic numbers suggests a new baseline, rather than a one-off administrative backlog .

As annual renunciations continue to exceed 200,000, the figures raise difficult questions for policymakers—not only about migration and citizenship law, but about how to retain talent and confidence in an increasingly mobile global workforce.