A comprehensive study of racism in Victoria has revealed that more than three-quarters of people from marginalised communities have experienced discrimination, yet only one in six ever formally report these incidents to authorities.

The research, conducted by Victoria University between 2022 and 2023, surveyed 703 adults and held focus groups with 159 participants from racially, religiously and culturally marginalised communities across the state.

The findings paint a stark picture of widespread racism, with those from African backgrounds reporting the highest rates at 91.1 per cent, followed by Muslim communities at 88.1 per cent and Jewish communities at 84.1 per cent.

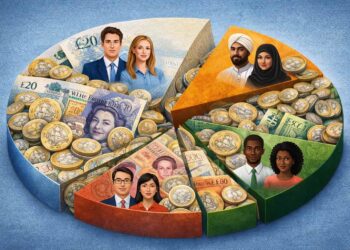

Among the diverse participant group, Indians represented the largest single nationality at 10.5 per cent of respondents, followed by Chinese at 8.1 per cent and Vietnamese at 5.5 per cent. Those describing their background as Indian or Sri Lankan made up 17.7 per cent of participants, while 21.3 per cent identified as Middle Eastern.

“The research shows that people of colour, particularly those from African and Muslim backgrounds, are facing persistent discrimination across all areas of life,” said lead researcher Dr Mario Peucker from Victoria University’s Institute for Sustainable Industries and Liveable Cities.

The study found that employment was the most common setting for racist incidents, affecting 56.5 per cent of those who had experienced racism in the past year. Public spaces including shopping centres (49.5 per cent) and public transport (37.8 per cent) were also frequent sites of discrimination.

Despite the prevalence of racist experiences, only 15.5 per cent of participants had ever formally reported an incident to an organisation. Around 63 per cent had only shared their experiences with family, friends or colleagues, while 21.1 per cent had never told anyone at all.

A Muslim woman in a focus group told researchers: “I would not know where to go first. The biggest reason [for not reporting] is probably not knowing. The obvious is the police station, but then, well, many of us already feel that police won’t do much.”

“The research shows that people of colour, particularly those from African and Muslim backgrounds, are facing persistent discrimination across all areas of life.” ~ Mario Peucker, Victoria University

The barriers to reporting were complex and interconnected. Three-quarters of participants didn’t know where or how to report racism, while 83.2 per cent found the process too difficult and time-consuming. Most concerning was that over 90 per cent believed “nothing would change” if they reported incidents.

Fear of consequences proved a major deterrent, with participants worried about impacts on their visa status, career prospects, or their children’s treatment at school. A participant from an Asian background explained they wouldn’t report workplace racism “because you don’t want to risk a bad performance review.”

The study also revealed cultural and psychological factors that discouraged reporting. Around 70 per cent of participants didn’t want to “cause trouble,” with some feeling their acceptance in Australian society was conditional on remaining quiet about discrimination.

A Chinese-Australian participant described the desire to fit in as fundamental: “We want to, and try to, fit in. And we have come to accept a little bit of tough treatment.”

For some Muslim communities, additional barriers included religious beliefs about leaving justice to God. As one participant noted: “My parents would sit me down and say: ‘these things happen, it’s okay, God will take care of it in the hereafter.'”

However, the research revealed that silence didn’t equal inaction. Many participants engaged in alternative forms of resistance, seeking support from their communities, confronting perpetrators directly, or using social media to share their experiences.

“While these voices may remain unheard in the broader public discourse on racism, they prioritise community support, personal wellbeing and agency instead of merely reacting to external calls to report racism,” the researchers noted.

Several participants suggested community-led solutions. A participant from a Mandarin-speaking focus group proposed that official support structures should be “complemented by Chinese grassroots community [groups] that can help people navigate the system.”

Similarly, a Somali-Australian woman argued: “As a community we need a platform where people can come and report, and we can then pass this on to the [human rights commission].”

The findings have significant implications for how Australia addresses racism. The researchers argue that current formal reporting systems are failing marginalised communities and may themselves constitute institutional racism by systematically excluding voices from public discourse.

“The reporting system fails many of those who are supposed to be the beneficiaries of these systems,” Dr Peucker said. “This highlights the inadequacies of formal reporting systems and the need for alternative, community-driven approaches to addressing racism.”

The study, funded by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, calls for better promotion of reporting pathways, more culturally safe systems, and greater recognition of community-centred responses to racism.

The research was conducted on the unceded lands of First Nations peoples across Victoria and included First Nations participants in the broader study.

Click here for anti-racism support services and reporting in Victoria, Australia.