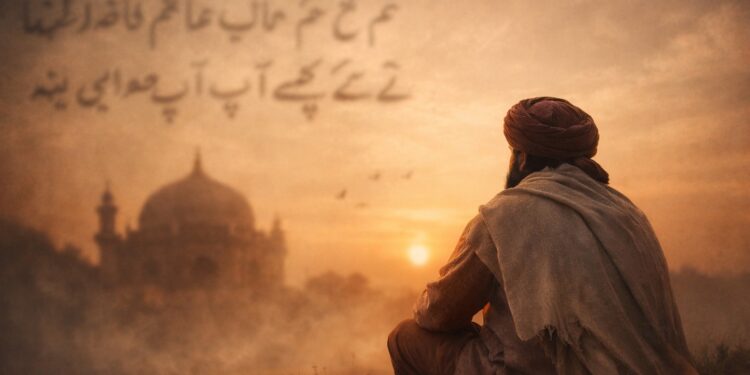

The 18th-century Sufi poet and philosopher Baba Bulleh Shah placed self-knowledge far above scholarly accumulation. He warned that one could drown in books and still remain a stranger to oneself:

Parh parh alam te faazil hoya

Te kaday apnay aap nu parhya ee na

پڑھ پڑھ علم تے فاضل ہویا

تے کدے اپنے آپ نوں پڑھیا ای نہ

You read and read, becoming learned and wise,

Yet you never once read yourself.

You mastered volumes to know everything,

But failed to read your own mind at all.

Bulleh Shah’s message is unambiguous: knowledge that does not turn inward remains incomplete. True wisdom begins not in libraries but in introspection. To “read the self” is to confront the authentic core that defines one’s personality, temperament, and moral compass.

The pivotal word here is authenticity.

Who are we, really?

We often use the word “authentic” casually — authentic cuisine, authentic art, authentic experiences. But when applied to the self, authenticity demands much more.

It requires a rigorous examination of our thinking, behaviour, and character. It asks whether our lives are genuinely our own or merely performances shaped to win approval.

Reading the self, then, becomes an act of identification. And the essential question arises: Who are we, really?

This inquiry has little to do with social status, professional success, or the roles assigned to us by family, culture, or society. Nor is it about fitting into identities others find acceptable or admirable. It is about recognising the valid, lived, and experienced Self — stripped of borrowed labels.

As the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard observed:

“The most common form of despair is not being who you are.”

Authenticity is an earnest attempt to live according to inner values rather than external expectations. It is a search for meaning anchored in the true Self — not one manufactured to win applause, avoid conflict, or secure belonging.

The urge to please others is not the authentic Self

During deep self-contemplation, one may encounter an uncomfortable truth: the self-image carefully constructed over the years is often false, or at least diluted. It may exist primarily to please others or to conform to social norms. Meanwhile, the authentic Self lies buried beneath layers of compromise, fear, and imitation.

The idea of self-authenticity arises from a sobering insight: human beings are frequently inauthentic — sometimes by choice, often by conditioning. Social relationships, cultural pressures, and inherited values subtly shape an artificial Self. Like chameleons, we adjust our colours for acceptance, survival, or gain.

The philosopher Erich Fromm captured this dilemma precisely:

“People think they are following their own desires when in fact they are obeying external pressures.”

Recovering the authentic Self earns credibility

Recovering the authentic Self therefore requires courage — and a radical re-evaluation of habitual lifestyles, cultural conditioning, and inherited ways of thinking. It means questioning not only society, but also long-held assumptions about who we believe we are.

Authenticity is not a fixed achievement. It unfolds over time. It matures through conscious practice — by choosing honesty over convenience, integrity over conformity, and inner truth over public validation. To be authentic is to align one’s actions with moral clarity and emotional sincerity.

As Carl Jung wisely noted:

“The privilege of a lifetime is to become who you truly are.”

Introspection, then, is not a one-time exercise but a lifelong reading process. Each chapter reveals more of the authentic Self.

Those who persist in this inner inquiry gradually earn something rare and invaluable: credibility. Frankness, straightforwardness, and honesty are not merely social or moral guidelines; they are natural expressions of authenticity.

To read oneself deeply is to live truthfully. And in that truth, the authentic Self finally comes home.